Samuel Beckett’s “Happy Days” has to be one of the toughest roles for a woman in modern theatre—it’s not only a virtual monologue (with a handful of interruptions) but the actor in question is limited to her voice, face and upper body in Act I, losing the use of her torso in Act II.

Any actor would be half daft to even attempt it, but I’m happy to report Dianne Wiest (at the Mark Taper Forum through June 30) is more than up to the challenge. Unlike Dame Peggy Ashcroft, who failed to engage the audience when I saw her do it in the West End of London in the ‘70s, Wiest immediately establishes a connection and never lets go. No mean feat for an actor initially buried to her waist in the earth, then mired up to her neck.

“Another heavenly day!” exclaims Wiest’s Winnie at the outset, though she doesn’t have much to look forward to other than clean her glasses, endlessly rummage through her handbag and ponder its contents. Any further attempt to describe the play’s “plot” or dramatic action seems absurd, given its focus on the subtlest of subtleties, and the nuances with which they are meant to be performed. Suffice to say Beckett’s minimalist drama provides a master class in acting when it’s done by an artist of Wiest’s ability.

Michael Rudko, to whose Willie the monologue is directed, seemingly does little more than read a newspaper during his brief appearances, but his literal and figurative absence is deceptive—as is the apparent simplicity of the play itself under James Bundy’s attentive direction. Izmir Ickbal’s scenic design is an imposing supporting player. This Yale Repertory Theatre production is a must-see for serious theatregoers, so rarely is the piece performed.

While I’ve had the misfortunate to see several bad productions of Beckett’s work, I have yet to see a weak staging of August Wilson. His plays may not make the same exacting demands on the performer, but they require the same sort of trust in the material—an actor has to buy into Wilson’s vision with his whole heart and soul or it doesn’t fly.

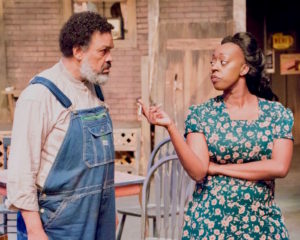

“Seven Guitars” (at Long Beach Playhouse through June 15) is, like most of Wilson’s plays, about a group of dreamers who talk a good game but don’t quite measure up when they’re at bat. This one takes place in 1948 Pittsburgh and centers on a gathering of friends mourning the sudden death of blues guitarist Floyd Barton, a colorful character whose bad decisions spell disaster.

In a first-rate ensemble cast, William Warren (as King Hedley, a street vendor) and Ebonie Marie (Louise, a neighbor woman) offer the standout performances, with Warren an unpredictable powerhouse. Rayshawn Chism (Floyd) is a strong and charismatic stage presence. Latonya Kitchen (Vera) is perfect as his on-and-off girlfriend; Justyn High (Louise’s niece, Ruby) is personable and charming in a role that might be unappealing in another actor’s hands.

Though the play runs well in excess of two hours, there isn’t a wasted moment, a scene that seems wordy or extraneous. Director Rovin Jay makes Wilson’s bawdy tragicomedy come alive as though he were born for the job. Andrew Wilcox’s sound design and Christine Bayer’s costumes help complete the picture.

Recent Comments