Q&A with Jordan

Get yourself a cup of coffee—I take mine with Hazelnut Coffeemate—put your feet up and get comfortable.

The Spike Jones book was probably one of your most ambitious projects. What inspired you to write it?

I had started collecting Spike’s records in my teens, scrounging for old 78s in neighborhood thrift stores long before eBay diluted the thrill of the hunt. In the ‘70s, I met three people who had worked with Jones—comedian Doodles Weaver, clarinetist Mickey Katz and writer Eddie Brandt. I decided to write an article but soon realized I had the makings of a book. But it wasn’t until I got a hot tip about a treasure trove of long lost memorabilia that the timing was right—imagine having Spike’s business correspondence just fall into your hands, revealing the inner workings of the organization he so skillfully concealed. I soon began to devote full time to tracking down and interviewing the survivors of the band, and drawing out their recollections of the man who assaulted popular and classical music with unparalleled artistry.

You got to know several of the character actors you interviewed for Reel Characters very well.

Yes, many of them became good friends who regularly invited me to their homes. Some, like Fritz Feld and Iris Adrian, were a lot like the colorful characters they played in films and TV, only more vivid in real life. Elisha Cook was nothing like the cowardly little victims he played in so many film noirs; he was fearless and outspoken. I cherish the memory of camping with him at his favorite getaway in the Sierras one weekend. Sam Jaffe could discuss any topic intelligibly but didn’t like to talk about himself; Anita Garvin was pure delight to visit and never lost her wonderful comic timing.

You’ve called The Beckett Actor the biggest adventure of your career. How so?

I first read Waiting for Godot when I was 18; I had no way of knowing it would change my life. When I heard about an actor named Jack MacGowran doing a one-man Beckett show in New York, a program cobbled together from Beckett’s stories, plays and novels, I was skeptical—how could anyone do that? I saw him do the show on stage in L.A. and ran backstage to meet him—I had to talk to him about Beckett’s work. When he suddenly died a year later, I decided to write a book about him. I did more than 100 interviews, including Roman Polanski in L.A., John Lennon in New York and Peter O’Toole in London. For a young writer with few credentials, I had a lot of chutzpah and determination.

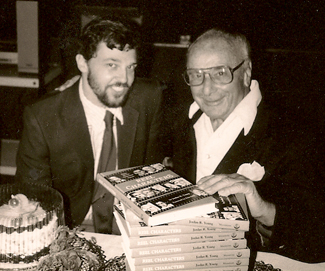

Jordan celebrating the publication of “Reel Characters” with actor Fritz Feld.

Jordan with film historian Kevin Brownlow at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival.

What prompted you to research and write Acting Solo?

Bettye Ackerman commissioned me to write a one-woman show for her about Edna St. Vincent Millay, the first woman—a Jazz Age feminist, no less—to win the Pulitzer for poetry. I began to think about all the solo performances I’d ever seen, including Hal Holbrook’s Mark Twain Tonight! and Julie Harris’s The Belle of Amherst; then I started researching people like Ruth Draper, who practically invented the form for the modern era and influenced Lily Tomlin and many others. Then I couldn’t stop—nothing new for me.

You’re also a playwright?

Yes, I derive great pleasure from using real-life characters or situations and taking dramatic license with them, which of course is out of the question in writing non-fiction. Writing for the stage exercises different muscles. If I have any facility for writing plays it’s in creating dialogue. I love to invent two or three characters, or take them from the real world, and put them in a room and imagine the conversation. I once adapted a series of one-act plays from the stories of Robert Louis Stevenson. Along the way I discovered he was a failed playwright; for all his genius in plots and plotting I feel his dialogue left something to be desired.

How did The Laugh Crafters come about?

My friend Randy Skretvedt came up with the idea for a book on dramatic radio. We did well over 100 interviews with actors, writers, producers, announcers, sound effects men, etc. I found the comedy writers in general to be the best raconteurs and started interviewing every one I could; I ended up talking to a dozen of them. Between them they wrote for virtually every comedian who worked in radio and early television in the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s. The comics all claimed they wrote their own scripts, except Jack Benny—he always credited his writers. Jimmy Durante’s writers got steamed at him once for implying to the press that he wrote his own stuff. They were working in a hotel and a cleaning lady came through; he introduced them to her and said, “These are the boys who write my material.” When she left he said, “See, I give you credit.”

King Vidor’s The Crowd was what you’d call a passion project?

Yes. Sometimes you have to forget about the market and go where your heart is. The Crowd is my favorite silent film. I interviewed both director King Vidor and Eleanor Boardman (the star of the film, and his then wife) for an article in the 1970s but could never sell the idea. When I stumbled on the material a few years ago, I realized I could do it as a book. Kevin Brownlow, the best friend silent movies ever had, was tremendously helpful, sending me all his research from decades ago. I also found lots of great material at the University of Southern California, including every draft of the script, original scenarios, telegrams, etc. I’m sort of spoiled now.

What’s your latest project?

A book on Roman Polanski, focusing on him as a filmmaker and his modus operandi. My intent is to transport the reader to the set of his offbeat classic, Cul-de-Sac—the film he has often called his best—during the making of the picture, so you’re looking over his shoulder and watching him at work. I interviewed Polanski and others decades ago but decided not to do the book unless he cooperated; happily he agreed and sent the shooting script, his sketches of scenes and characters, and even the daily call sheets. I tracked down the assistant director (one of the last survivors of the crew), and did a terrific interview with him.

What’s the secret to getting inside your subject?

For me it’s interviewing people who were there at the time, whether it’s people who went to high school with your subject, worked on films or stage productions with them or what have you. I’ve been incredibly lucky in one sense, but I’ve also worked like the devil to get people to talk to me. I had to call John Lennon’s office day after day before he made himself available; George Marshall made me chase after him for weeks, calling him repeatedly, before he finally sat down with me to talk about directing Laurel and Hardy in the 1930s. My “secret” for getting a great interview is to make a good impression, establish a rapport and then shut up and let the subject do the talking. As long as they don’t go off on a tangent, I just let them talk.